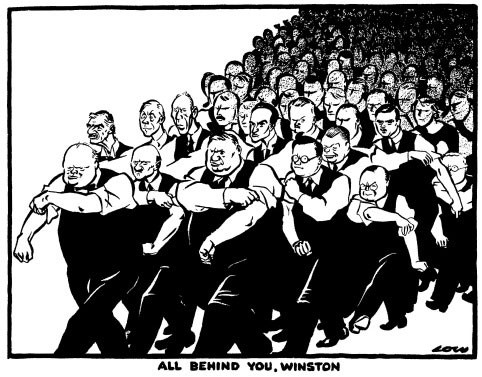

Articles about some of the characters featured in 'All Behind You Winston'

Fri 12th Aug 2016

I’ve written a series of articles about some of the characters and themes in my new book All Behind You, Winston, which you can read here.

- The cartoon – and the cartoonist – which inspired the title of the book (in the Evening Standard, April 2016). https://www.standard.co.uk/comment/comment/roger-hermiston-in-our-darkest-hour-the-standard-s-great-cartoonist-rallied-the-nation-a3218206.html

- A portrait of Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food who ensured the people of Britain did not starve. http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/liverpool-blitz-1941-new-book-11179611

- A piece about Arthur Greenwood, deputy leader of the Labour Party, who crucially backed Churchill in his dispute with Lord Halifax over whether to sue for peace with Hitler. http://www.yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk/news/opinion/roger-hermistonarthur- greenwood-the-yorkshireman-who-spoke-for-england-in-churchills- darkest-hour-1-7885538

- One of the more astonishing initiatives in the early days of the Churchill administration was the Anglo-French Declaration of Union – which would have seen Britain enter into full economic and political partnership with France (‘No Longer Two Nations But One’). https://thelionandunicorn.wordpress.com/2016/06/04/no-longer-two-nations-but-one/

- There were only two women (out of 84) in Churchill's administration - Ellen Wilkinson, the fiery Labour MP for Jarrow, and Florence Horsbrugh, Conservative MP for Dundee. Although junior ministers, they both played vital roles on the Home Front, particularly during The Blitz. I recounted Horsbrugh's career and WW2 experience in this article for The Herald (May 2016).

'In July 1939 Florence Gertrude Horsbrugh’s early performances at the despatch box as a new minister in Neville Chamberlain’s administration won her glowing reviews. ‘She has brains, capacity and a pleasing personality’, wrote the Daily Despatch. ‘Her words were beautifully articulated’, ventured The Star. From the Daily Mail there was an impressive comparison; ‘She is a feminine Churchill. She goes after facts, and is not afraid to attack her own party chiefs when necessary’.

This daughter of an Edinburgh chartered accountant was already one of the best-known woman MPs, having gained the accolade of moving the address to the King’s Speech in 1936, and then being interviewed about it afterwards on the brand new medium - television. She would go on to fulfil her potential by becoming the first women to serve in a Conservative cabinet as Minister of Education when Churchill finally elevated her to the top table in September 1953. But despite all her achievements in an era where women struggled to achieve prominence in a profession dominated by men, she was somewhat overshadowed by her more colourful contemporaries like Labour firebrand Ellen Wilkinson, social reformer Eleanor Rathbone and the flamboyant Lady Nancy Astor.

In particular, Horsbrugh’s sterling contribution to Churchill’s wartime coalition government has been hugely overlooked. When the new prime minister finished drawing up his list of eighty-four ministers, there were just two women on it – 48-year-old Wilkinson, who became a junior minister at the ministry of pensions (she would soon move to the Home Office) and 50-year-old Horsbrugh, who Churchill allowed to continue in her post as parliamentary secretary at the ministry of health. Churchill had his doubts as to whether Horsbrugh was up to the task. ‘Can you bear it? Can you stand up to it?’, he asked her during their job interview on 17 May 1940.

If the prime minister had qualms, few others in his government did. ‘I do so like that little spitfire’, minister of information Harold Nicolson (also one of the war’s great diarists) observed of Labour’s Ellen Wilkinson. ‘She and Florence Horsbrugh are really the only two first-class women in the House. I should like to see both of them made Cabinet ministers’. Given Churchill’s historical discomfort with the presence of woman in the Commons this was never very likely, but at least he encouraged them in the crucial roles they both played in The Blitz and beyond.

Horsbrugh had first come to public attention in the First World War when her pioneering work in developing a national network of kitchens and canteens won the approval, among others, of Queen Mary, and gained her an MBE. Once the Second World War began in September 1939, she was tasked with one of the most crucial roles in civil defence – arranging the successful evacuation from the major cities of one and a half million women and children. This complex, emotionally exacting exercise – effectively one of the biggest social experiments in British history – was managed with outstanding efficiency by Horsbrugh and her colleagues at the Ministry of Health.

Then in the autumn of 1940 Horsbrugh turned her attention, along with Wilkinson, to the victims of the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign. She organised casualty clearing stations in London, set up hostels for those rendered homeless and ensured the smooth running of rest centres. With Wilkinson she was also responsible for health and sanitation in London’s underground shelters, with both women sitting on a special ad-hoc committee on the matter which Churchill himself chaired (the prime-minister’s wife Clementine had helped stir his interest in this area). Horsbrugh also took it upon herself to completely restructure the British Civil Nursing Reserve.

But it was the destruction of Coventry in November 1940 that saw Horsbrugh at her compassionate and resourceful best. As soon as she had the first inkling of the severity of the raid, she took her own car and drove into the city even before the flames had died down. In the following weeks her task was to once again evacuate women and children, and find beds for the thousands who had been made homeless: the Daily Mirror described her role as that of ‘mothering the city’. A few years later, when Horsbrugh visited her old boss Malcolm MacDonald, the former Minister of Health, in Canada, he acclaimed her to the press as ‘one of the heroines of Coventry’.

Horsbrugh had what the Evening Argus, Brighton once described as a ‘magnificent contralto voice, clear, resonant and at times thrilling’, and this asset ensured she was a regular contributor to BBC Radio in wartime, when she gave talks – amongst other subjects - calling for nursing volunteers, took part in discussions about the future of the health service, and appeared on Any Questions. A correspondent to the Dundee Courier was moved to write, ‘The broadcast of Miss Florence Horsbrugh the other day was an intellectual feast. One got time to listen and inwardly digest every word and sentence of her appeal’.

In the early months of 1944 she was involved in much of the preparatory work for the coalition government’s White Paper on health, which was the blueprint for a truly national service. Horsbrugh battled to assuage MPs’ doubts about the independence of doctors and the future of voluntary hospitals, concluding a rowdy Commons debate in March with a rousing finale in which she hoped people looked back on 1944 as the year when ‘at at time of an increase of suffering, of wounds and maiming and crippling, we in this House launched a scheme to allay suffering … to do something constructive for the people of this country’.

Then in April 1945, along with deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and Ellen Wilkinson, she travelled to San Francisco to represent Britain at the conference to set up the new United Nations. Her contribution was greatly valued, especially by Britain’s Ambassador to Washington Lord Halifax, who wrote to thank her afterwards, saying, ‘You have been a tower of strength and wise counsel: and we shall miss you very much’.

Horsbrugh’s career as MP for Dundee (from 1931) and government minister dominated her life, and she left little time for relaxing pursuits.

‘She is a glutton for work’, the Liverpool Daily Post correspondent noted in July 1939. ‘I have never known her of having any particular recreations, but when the opportunity presents itself she loves to get away into her garden and do a bit of digging’.

She was never a feminist – if such a term resonated in the 1940s – once telling the Sunday Graphic, ‘I want to forget that I am a woman doing my job. It doesn’t help for people to emphasise that somebody doing a certain job is a woman’. Shades of the second woman to become a Conservative cabinet minister in 1974 – Margaret Thatcher.

Horsbrugh never married, and newspapers – in the condescending style of the time – would often refer to her as the ‘Spinster MP’ or ‘Maiden Aunt’. Lady Astor rather maliciously and bitchily referred to her as ‘Horseface’, but her close friends knew her as ‘Fluff’. Tall, smiling and invariably unflustered, with a ‘humorous twinkle in her eye’, she brought an impressive mixture of ministerial authority, political sagacity, feminine gentleness and maternal fussiness to her wartime duties.

In many ways, to coin a well-worn phrase, 1940-45 was her ‘finest hour’. Her stint in Churchill’s cabinet in the 1950s was troubled, as the government’s priorities were by then on housing, not education, and she was denied the resources to fund extra secondary school places or rebuild crumbling buildings.

Created a life peer in 1959, Baroness Horsbrugh attended the House of Lords as regularly as she could, demonstrating her great powers of debate, until frailty overtook her. She died in 1969, aged 80. A woman who preferred low tones to high lights, understatement to exaggeration, Horsbrugh was an admirable lieutenant rather than a pioneer. But her valuable role in Churchill’s ‘Great Coalition’ should not be forgotten.'