DARKEST HOUR

I contributed a couple of pieces for the Daily Telegraph ahead of the new Churchill film, Darkest Hour. One was how Churchill rallied a nation on the brink of disaster, while the other was about how he outmanouevered Lord Halifax, who wanted peace negotiations to be explored...

DARKEST HOUR

On the morning of Tuesday, May 28 1940, Britain was facing her greatest external threat since Napoleon’s army stood on the clifftops at Boulogne one hundred and thirty-five years before, awaiting the order to cross the English Channel.

Now it was Hitler who had Western Europe at his mercy. Holland and Luxembourg had been crushed in the previous fortnight; at dawn that day came the news that the Belgian army had surrendered, making the position of the British Expeditionary Force, desperately attempting to evacuate Dunkirk, ever more perilous.

In cabinet that morning the First Sea Lord reported that 11,400 troops had managed to make it back to England overnight. But that still left over 300,000 British and French soldiers to bring home in Operation Dynamo – and few believed more than 50,000 would survive to fight another day.

Not that Britain was in any state to adequately defend herself. General Sir Edmund Ironside, the new Commander-in-Chief of the UK’s Home Forces, wrote gloomily in his diary; ‘The state of the armament is catastrophic. I hope it will get better in a week or two. Hope we get a week or two…’

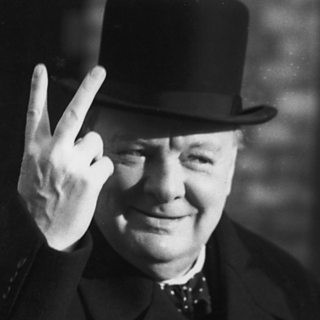

Winston Churchill, just eighteen days into his premiership, confronted not just military disaster, but a fierce political tussle in his war cabinet with the ‘old guard’. His position at the head of government was fragile: he had landed in 10 Downing Street by means of – effectively – a parliamentary coup, and there were many in Parliament, his own Conservative party and the opposition alike, who felt that the ‘Great Adventurer’ of British politics was a reckless choice for leader at the country’s bleakest moment.

But cometh the hour, cometh the man. What Churchill did on that spring day not only secured his position as premier, but set his country on a lonely, defiant path of opposition to Nazi Germany. First, he headed to the Commons chamber where – following the urging of his Information Minister, Duff Cooper at the morning cabinet – he spelt out the grim reality of the Dunkirk retreat, telling MPs (and by extension, the British public) that the situation facing our troops was ‘extremely grave’, and that the House should prepare itself for ‘hard and heavy tidings’. But, in a rallying call at the end of his statement, ‘nothing’, he proclaimed, ‘should destroy our confidence in our power to make our way … through disaster and through grief to the ultimate defeat of our enemies.’

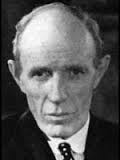

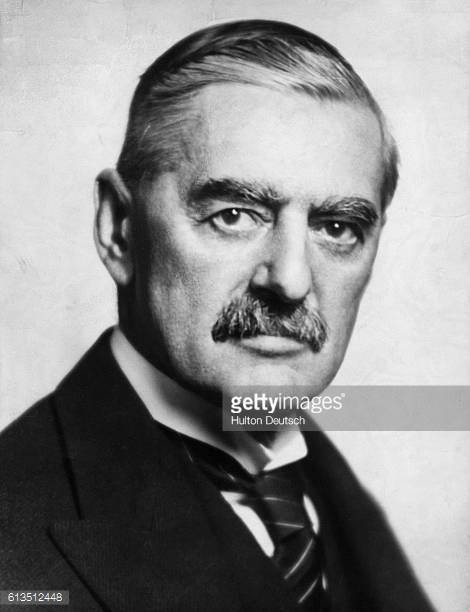

Then, in the course of a series of dramatic meetings in the Prime Minister’s room behind the Speaker’s Chair – of both the war cabinet and his ‘outer’ cabinet – he set about skillfully and methodically dismantling opposition to his desire to face down the Nazi threat. In five tense cabinet discussions in the previous two days, foreign secretary Lord Halifax – supported sporadically by the ousted Neville Chamberlain – had put the French case for turning to Italy (hostile, but still neutral) as a mediator in possible negotiations with Hitler.

Now, aided by quiet but effective support from his Labour war cabinet colleagues Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood, and bolstered by a rousing reception from his junior ministers, Churchill eventually wore down the ‘Holy Fox’, who had been his chief rival for the premiership.

‘Nations which went down fighting rose again, but those which surrendered tamely were finished’, he told a chastened Halifax. At twenty minutes before midnight Churchill messaged French premier Paul Reynaud to reject his proposed acceptance of Italian mediation.

In three weeks France would follow Belgium and surrender - leaving Britain alone in the struggle against Nazism. But the Darkest Hour had passed. The ‘miracle of Dunkirk’ had taken place – and Churchill had stiffened the nation’s sinews.

OUTFOXING ‘THE HOLY FOX’

When Winston Churchill walked in to the Cabinet Room at No 10 Downing Street shortly after 4.30pm on Thursday, 9 May, it seemed for all the world that his main rival, the experienced Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, would be confirmed as the new Prime Minister-in-waiting. Premier Neville Chamberlain - fatally wounded after a Commons debate on the conduct of the war - wished his closest colleague to succeed him, the Labour Party appeared to prefer him, and the King certainly wanted his old friend to take the job.

Yet, unexpectedly, half an hour later, after Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill (Lord of the Admiralty) and Tory Chief Whip David Margesson had concluded their deliberations, it was the ‘Rogue Elephant’ who emerged as the man to replace Chamberlain.

With no official minutes taken, the most fateful meeting in British political history remains a subject of immense fascination and contention to this day. Had Churchill been schooled to remain strategically silent by close friend Brendan Bracken and new-found ally Kingsley Wood when Chamberlain asked him if he would support Halifax? Did the Foreign Secretary really have an acute stomach ache which affected his mood on the day?

Yet if the exact details of this remarkable meeting of the Government hierarchy – for it was them, not the electorate, deciding on the country’s next leader - remain a matter of Westminster folklore, its outcome was easier to interpret. Churchill was up for the job, whereas Halifax, for varying political and personal reasons, wavered.

‘Quite apart from Winston’s qualities as compared with my own at this particular juncture … Winston would be running Defence … and I should have no access to the House of Commons’, Halifax reflected in his diary that night. ‘I should speedily {have} become a more or less honorary Prime Minister, living in a twilight zone just outside the things that really mattered.’

This was how Halifax justified his reluctance to seize the crown to himself. More likely is that, at the very moment of opportunity, he simply feared that the burden of responsibility would prove too great for him to bear. For Churchill, the mindset was utterly different; ‘I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and this trial.’

These two giants of British politics were both sons of aristocrats (one born in a palace, the other in a castle), and both suffered from speech (lisp) impediments. But there was little else to unite them in character and disposition. The immensely tall, cadaverous looking Halifax, born with a withered left arm and no hand, was stately, courteous, attentive, principled and coolly logical. The Churchill family dubbed him ‘The Holy Fox’ after his twin passions of Anglo-Catholicism and fox-hunting – but implicit in the nickname was the cunning he demonstrated in the political arena.

Churchill, still building alliances - and his reputation – in the early weeks of his premiership, needed all of his own guile to outflank his rival in the War Cabinet. Whilst he had been the most stalwart, the most eloquent opponent of appeasement on the backbenches in the 1930s, Halifax – who had met Hitler in 1936 – felt his quest for a diplomatic settlement with Germany satisfied the public yearning for peace.

Those disagreements remained, and were fought over ferociously, around the Cabinet table in late May 1940. For the foreign secretary, there was nothing dishonorable in wanting to stitch together a deal that could save the Allied armies in the field, and safeguard Britain’s independence and that of her Empire. Churchill’s view, expressed to Halifax over the Cabinet table on 27 May, was that we must not be ‘dragged down the slippery slope with France.’

‘The best help we could give to M. Reynaud (French premier) was to let him feel that, whatever happened to his country, we were going to fight it out to the end.’

In the end Churchill’s arguments prevailed, but it was a close-run thing. It was only six months later, after Chamberlain’s death and with his own status enhanced after the Battle of Britain, that he felt free to shift Halifax from the centre of political gravity - and off to America as Ambassador to Washington.