HOW I CAME TO WRITE 'TWO MINUTES' (BLOG FOR BITEBACK)

Two Minutes to Midnight – 1953, The Year of Living Dangerously is an account of one of the most gripping, epoch-making twelve months in the Cold War. Author Roger Hermiston explains how he came to write about this year….

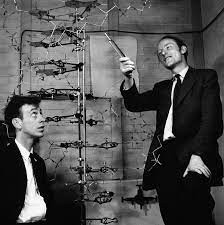

Ask someone for one important fact about 1953 and they might point to it being the year of the Coronation of our present Queen. If they are sports lovers, they could cite England regaining the Ashes at cricket, or the famous (Stanley) Matthews FA Cup final. Ask a scientist and they would tell you it was the year of the discovery of DNA by Cambridge scientists Crick and Watson. Then of course, there was the first ascent of Everest by Hillary and Tensing.

My initial fascination with 1953 began with the political crisis at home over Winston Churchill’s stroke in the summer. The extraordinary cover-up of the Prime Minister’s illness – unthinkable in this era of press scrutiny and social media – has been written about before, and a half-decent drama (with Michael Gambon as Churchill) made about it.

But I felt a definitive account of how a small group of ministers, aides and civil servants kept the nation in the dark about their premier’s brush with death, and how they ran the country in his absence – along with that of his deputy, foreign secretary Anthony Eden, also seriously ill – could make for compelling reading.

And so it does – hopefully! – in Chapter 7 of Two Minutes, entitled ‘The Emergency Government’. But as I discovered when starting my research, there was much, much more to say about this twelve months that had previously been labelled as one of the more monochrome years in the Cold War, not to be compared with the likes of 1948 (Berlin Blockade), 1956 (Suez and invasion of Hungary), 1962 (Cuban Missile Crisis), or 1983 (the Able Archer war game that nearly went disastrously wrong).

At the start of 1953 there was still no end in sight in the Korean War, which pitted America against China and the Soviet Union (on land and increasingly in the air) in a highly dangerous proxy conflict. In March Joseph Stalin died, leaving the Western powers in a state of confusion about how to deal with the new men in the Kremlin.

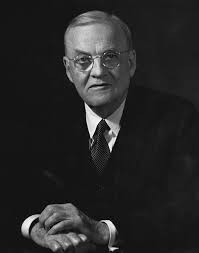

The ‘Red Menace’, threatening America abroad and at home, still loomed large in the minds of its citizens in 1953, kept there by the highly influential Communist witchfinder-in-chief Joe McCarthy. The US government, with new Republican President Dwight Eisenhower backed by his hawkish Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, saw no reason to drop their guard because of Stalin’s departure.

However Churchill, the man who had coined the term ‘Iron Curtain’, now wished to draw it back and was desperately keen to embark on a new policy of ‘easement’ (detente) with Stalin’s successors. Eisenhower and Dulles were having none of it, and this tussle between the White House and Downing Street is a key theme of the book.

In 1953 Churchill sent a warship to the Falklands, the intelligence services of America and Britain plotted a successful coup in Iran, America was gradually being drawn into France’s disastrous war in Indo-China (soon to be Vietnam), and Britain elected not to get involved with moves towards European economic and political unification. All of these events, hatched in 1953, would have profound consequences in years to come – and still do so today.

But above all, it was the shadow of the mushroom cloud that loomed over this year. The United States had successfully tested her own H-bomb on the eve of 1953 – and the Russians responded with her own thermonuclear device in August. Throughout the year, America conducted A-Bomb tests in the Nevada desert – one of them live on television. In Korea, Eisenhower’s administration debated whether to drop tactical A-bombs on the enemy on seven separate occasions between February and May.

All this led to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists to move the hands of its ‘Doomsday Clock’ to two minutes to midnight, the closest it had yet calculated the world was to nuclear Armageddon. 1953 certainly was the year of living dangerously, and I hope my book reflects what a tense, fascinating twelve months it was.