ALTERNATIVE PROLOGUE

Fri 2nd Sep 2016

Early on in the process of writing of All Behind You, Winston I crafted this piece as the opening - the Prologue - of the book. It eventually ended on the cutting room floor, but I reproduce the original, unedited version here, because it gives a flavour of the atmosphere in Churchill's cabinet, and fleshes out some of the principal characters who sat round the table with him in the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street...

PROLOGUE

The Cabinet Room,

10 Downing Street,

Monday September 29, 1941.

5pm

There were, as yet, no broad sunlit uplands in sight. But just over two years into the war, the Prime Minister prepared to chair one of his regular Monday War Cabinet meetings in a mood of cautious optimism. In order to reflect it for Parliament and for the country’s benefit, he had inserted one of his typically felicitous phrases into the speech he would deliver to the House of Commons the next day. ‘We have climbed from the pit of peril on to a fairly broad plateau’, was his assessment of Britain’s position.

The nation was no longer alone. The Soviet Union was an ally – although the German army now had Moscow in its sights, one hundred days after Hitler launched ‘Operation Barbarossa’. Churchill’s assiduous wooing of America had resulted the previous month in an ambitious statement of joint principles and values, the Atlantic Charter; hopes were rising that President Roosevelt would carefully guide his country into the conflict any time soon.

With the heavy bombing of London and other British cities over – for the moment – Churchill and his colleagues had been able to leave their subterranean world under Storey’s Gate, from where the war had been largely conducted throughout the autumn and winter of 1940 and 1941. This War Cabinet meeting, like most since the spring, was to be held in the traditional gathering place, the very heart of British Government decision-making ever since Sir Robert Walpole, the first ‘First Lord of Treasury’ (Prime Minister was a derogatory term in those days) took up residency in the 1740s.

For those ministers with a sense of history, arriving at the Cabinet Room never failed to elicit a frisson of anticipation. An empire was built, colonies lost, wars plotted, and the people enfranchised in this ‘cramped, close space’, as Lord Salisbury, Prime Minister in the 1880s, described it.

Just inside the entrance stood two Corinthian columns, supporting a moulded entablature, which wended its way around the room. These grand pillars were put up in the 1790s, at the request of William Pitt the Younger, when the room was extended.

A 25-foot long table dominated much of the rest of the space, around which stood some 20 or so curved, leather-upholstered mahogany chairs, dating back to William Gladstone’s time. Only the Prime Minister’s chair, with its back to the mottled grey, marble fireplace, had arms. Each Cabinet minister was allotted a chair according to rank, and the black blotters, inscribed with their titles, marked their places.

On two of the walls were large bookcases that housed the Prime Minister’s Library. It was a tradition, initiated by Ramsey MacDonald in 1931, that each Cabinet minister on leaving office should donate a book to the collection. On the wall at the far end of room hung a large map of the war.

The picture above the fireplace, by the French artist Jean-Baptiste van Loo, captured the physical likeness and much of the character of No 10’s first occupant. Sir Robert Walpole’s thick arched eyebrows, brown eyes, protruding lower lip, double chin and ruddy complexion were all on show, as was his dress, the black and white robes of the Chancellor and garter ribbon and star, indicating his membership of the Order of the Bath.

Churchill had a soft spot for his ancient predecessor, regarding him as the ‘first great House of Commons man in British history’. He carried with him an image of Walpole, during the last days before his fall, sitting in Downing Street for hours on end, ‘alone and silent, brooding on the past’. In his darker moments, perhaps he envisaged a similar fate for himself; the echoes of history were never far away in his mind.

On that afternoon in September, the 41st Prime Minister, sitting directly beneath the portrait and preparing to chair the War Cabinet meeting, was wearing something very different - his favourite piece of clothing, as unconventional and utilitarian as Walpole’s was formal and ostentatious.

Churchill was in his green velvet ‘siren suit’, a zip-up-all-in-one outfit designed by him before the war, in imitation of the boiler suits worn by his fellow bricklayers at his country house, Chartwell. His family, mockingly yet affectionately, called it his ‘rompers’.

It was a generously cut garment, including substantial breast pockets, which housed the several cigars he invariably got through in the course of a Cabinet meeting. A large coal bucket sat behind his chair, ready to receive the butts he carelessly discarded over his shoulder.

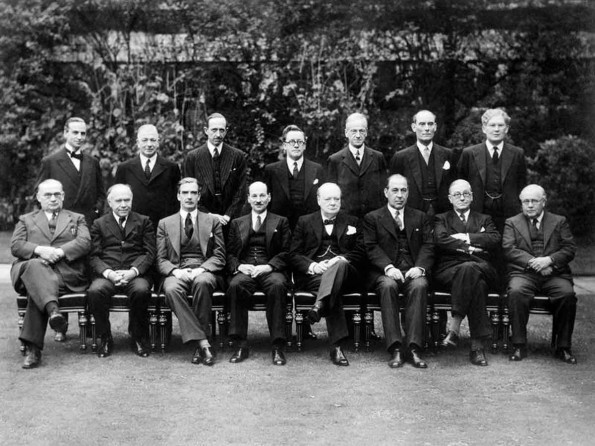

Despite the constant preoccupations of war, Churchill had found time for some relaxation that afternoon. No 10 had resounded to the sound of laughter and the clink of glasses from a party held for one of his Private Secretaries, Jock Colville, who was leaving to train as a fighter pilot in the RAF. The Prime Minister had affably posed for a photograph with Colville and the rest of his secretarial team in the garden, suggesting that the Cabinet should also be recorded on camera. ‘They’re an ugly lot – but still…’ he joked.

The number of War Cabinet meetings a week could vary, but the ‘Monday Parade’, as it was known, was a permanent fixture in the diary, with the largest attendance. Here, military chiefs would present a detailed statistical picture of the losses and gains of men and machines, and then courses of action could be debated and decided.

On this day, in addition to the War Cabinet of seven and three Chiefs of Staff, it was customary for a number of members of Churchill’s ‘outer’ Cabinet, together with one or two ministers ‘below the line’ (Parliamentary Private Secretaries), to be invited to join the meeting if they had specific interest in any of the items on the agenda.

There were twenty with Churchill around the table that day, nineteen men and, unusually, one woman – Florence Horsbrugh, Parliamentary Private Secretary at the Ministry of Health. If it went true to form, all would be guaranteed a memorable occasion.

At this stage of the war, Churchill was an utterly commanding, almost dictatorial presence among his colleagues. His unrivalled experience in Government – he had held nearly every important Cabinet post bar that of Foreign Secretary over the three previous decades – cloaked him in authority. His inspirational leadership in the past 16 months, steering a battered nation through the Battle of Britain and The Blitz, only added to his aura.

The Prime Minister approached each new Cabinet meeting as if he was an author as well as a leader, viewing it as an exercise in writing fresh lines in the story of the war – a book, he never tired of telling people, he would one day write himself. So, amid the practical discussion of events and strategy, he liked to embellish proceedings with relevant passages of his own very romantic view of history, discourses in military tactics, and sprinklings of his often-unorthodox philosophy of life. He was at times rehearsing for the big set piece speeches in made in the House of Commons.

‘His real tyrant is the glittering phrase’, observed Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies after attending a War Cabinet in early March. ‘It is so attractive to his mind that awkward facts may have to give way’.

Churchill demanded to be the main character on the page, the one who opened the discussion, the one who dominated it, and the one who decided its outcome. In that frame of mind, he would often brook no opposition.

Yet he also relished an argument, born of years of partisan debate in the House of Commons, and a War Cabinet meeting was usually enhanced if those around him rose to the challenge and took him on. But it was no place for the hesitant, and heaven help even the stronger willed opponents if they had not taken great care to marshal their arguments. If they had, the thrust and counter-thrust of debate would elevate the matter at hand and lead to fruitful decision-making.

Interminable monologues were not uncommon. Then on occasions, the Prime Minister would arrive having failed to read the briefing paper on a particular subject, and an hour’s discussion would ensue before he felt he had got to grips with it. This was hugely irritating to colleagues, but for Churchill it was often a conscious ploy to play for time in order to ultimately derail a policy he disapproved of.

More often than not, though, the ‘Old Man’ enlivened his colleagues’ day and set them on their way with renewed purpose. ‘We go to bed at midnight, conscious of having been present at an historic occasion’, was the verdict of Ellen Wilkinson, the only other woman in Churchill’s government.

Of those around the table that day, the pugnacious Ernest Bevin was the Prime Minister’s only rival in verbosity. Barrel-chested and bearlike, ‘Ernie’ would lumber into the Cabinet Room, cigarette at the end of his mouth, and prepare to take a full part in proceedings. He had a habit, in meetings, of taking a comb out of his jacket and running it through his thin hair; and an even more disconcerting one, of taking his false teeth out, slipping them into his pocket, and then inserting them again.

The country’s foremost trade union leader, earthy, opinionated, at times bombastic, he would ‘hold forth at great length…in the most egotistical, artistic way, much in the same way as Winston would’. This farm worker’s son, who was orphaned at the age of eight, was now as Minister of Labour and National Service in a position of immense power.

Through the Emergency Powers Act of May 1940, Bevin had effectively been granted absolute authority over the lives of every civilian between the ages of 14 and 64. ‘I suddenly found myself a kind of Fuehrer with powers to order anyone anywhere’, he said, joking to an audience of trade unionists.

Clement Attlee, Lord Privy Seal and de facto Deputy Prime Minister, usually sat on Churchill’s left, lighting his pipe to add to the cloud of smoke emanating from Churchill’s cigar.

A lawyer’s son with a public school education, Attlee was physically and temperamentally diametrically the opposite of his Labour ally. A small, bald man with a sizeable, well-trimmed moustache and round, steel rimmed spectacles, he had a quiet persona and apparently imperturbable manner.

Although infrequent, his contributions were always to the point, in his inimitable, terse, clipped manner of speaking. On the best days he regarded Churchill’s cabinets as ‘great fun’, but they were also frustrating to a man of economy and precision in all things. It wasn’t unknown for him to compose a few lines of poetry while waiting for the leader’s wilder monologues to blow themselves out. His great strengths, at this stage of the war, were seen at their sharpest in committee rather than in the War Cabinet.

Sir John Anderson, Lord President of the Council, was a crucial figure in both spheres. A brilliant student at Edinburgh University, he gave up a scientific career for one in the Civil Service, where he scaled the heights in senior roles in the Home Office, in Ireland, and then as Governor of Bengal. He had entered Parliament in 1938 as an Independent, free from any party label although his instincts were conservative.

A tall man invariably dressed in a black coat and wing collar, Anderson had a large, coldly impressive face that barely moved a muscle, and a voice as dry as tinder; his manner could occasionally lapse into pomposity. In later years his more jowly face took on a lugubrious countenance, uncannily similar to the bloodhounds he loved to breed. On this day he was in excellent heart, as at the weekend he had a marriage proposal accepted by Ava Wigram, society hostess and widow of Churchill’s friend Ralph Wigram.

Like Attlee, a man of comparatively few words, Anderson was nonetheless listened to attentively because of a muscular mind, encyclopaedic knowledge across a range of domestic subjects, and a prodigious memory. He would argue his case in Cabinet soberly and efficiently, in the manner of the impartial civil servant he was by training; but like many around the table, he rarely dared to cross Churchill.

The fourth, vital, member of the War Cabinet in attendance that day was Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. His experience on the battlefield in this group of men - and woman - was second to none; he was awarded the Military Cross for his actions in June 1917 for courageously rescuing his wounded sergeant under fire at Ploegstreet on the Western Front.

Bestowed with handsome looks and possessed of an urbane manner, Eden’s political rise had been meteoric between the wars, culminating in him becoming the youngest-ever Foreign Secretary at the aged of 38 in Stanley Baldwin’s National Government in 1935.

Just under three years later he resigned over the Munich Agreement and then, in the political wilderness, he became the acknowledged leader of a group of disaffected, anti-appeasement Tory MPs derisively dubbed the ‘Glamour Boys’ by the party’s Chief Whip David Margesson.

Churchill had appointed Eden Secretary of State for War when he became Prime Minister in May 1940, and six months later, when he felt free to do so, returned him to his natural place at the Foreign Office.

Of these four most powerful members of the assembled War Cabinet, Eden had the closest relationship with Churchill because of their joint prosecution of the diplomatic and military side of the war effort. He would attempt to persuade and if necessary argue with the Prime Minister over his wilder schemes, but was inclined to do it in private and not necessarily display his hand at Cabinet.

Two others around the table that day commanded attention, one because of his personality and unique influence, the other because of the novelty of her gender - although she too was talented and resourceful.

Brendan Bracken was an imposing, unusual looking man – tall, burly, bespectacled, with a big, pale face, brown eyes and a shock of wiry red hair that seemed to stretch over his forehead like a wig. There was a simian-like quality about him that both attracted and repelled.

Conservative MP for North Paddington since 1929, Bracken was Churchill’s Parliamentary Private Secretary at the beginning of the war, before being promoted to the Cabinet as Minister of Information in July 1941. He was one of the more extraordinary individuals to penetrate the inner sanctum of power in British politics; no one was quite sure where he had come from, and what he had done along the way.

Bracken actually hailed from County Tipperary, Ireland, the son of a Roman Catholic builder and monumental mason. An unruly teenager, he was despatched to Australia where he spent a precarious, nomadic three years, working on a sheep farm, travelling, reading avidly and visiting religious establishments.

When he returned, a career as a teacher was quickly abandoned and instead he headed for London, where he began to carve out a career as a newspaper editor and magazine publisher.

Bracken first met Churchill in 1923, and despite a 25-year age gap, built up a close relationship. The older man took to the younger because of a similarly adventurous spirit, romantic view of history, and a facility with words; Bracken had a charm and a wit that would lift Churchill out of the most melancholic of moods. It was whispered in the clubs of Whitehall that he was the Prime Minister’s illegitimate son – a rumour utterly without substance.

Bracken was the joker in and around the Cabinet Room, swapping stories, frequently passing notes across the table in meetings. Churchill would treat him with an indulgence he denied most others. The mischievous Irishman was also the creator of cruelly appropriate nicknames for his Cabinet colleagues - for example John Anderson was ‘God’s Butler’ or ‘Maestro Pomposo’, Anthony Eden was ‘The Film Star’, and Chancellor of the Exchequer Kingsley Wood, present that day, was ‘Little Joe’.

In the group of junior ministers was Florence Horsbrugh, who had made the transition from Chamberlain to Churchill cabinets and was making her first appearance at the latter. Conservative MP for Dundee since 1931, Horsbrugh had consistently impressed her colleagues with confident speeches in Parliament, delivered with a fine, contralto voice. She had played a vital role in the mass evacuation of over a million mothers and children at the beginning of the war, travelling the length and breadth of the country to see them settled.

In The Blitz, she toured England studying the troubles of air raid victims, overseeing new hostels for those rendered homeless, and completely reorganising the British Civil Nursing Reserve. A woman who preferred low tones to high lights, understatement to exaggeration, Horsbrugh had brought to her task in the Health Ministry an ‘impressive mixture of ministerial authority, political sagacity, feminine gentleness and maternal fusiness’.

It took special character for a woman to force herself into the male preserve of British government. Horsbrugh and her colleague Ellen Wilkinson were untroubled by their isolation and more than capable of holding their own. Horsbrugh chain-smoked like the best of them round the table that day.

These then were some of the key characters Churchill relied upon to help him conduct the war, particularly on the Home Front. One crucial figure was missing – the Prime Minister’s old friend Lord Beaverbrook, who, along with Averell Harriman, President Roosevelt’s Special Envoy to Europe, was starting his second day of talks with Stalin in Moscow.

Churchill began the meeting in grumbling fashion. His irritation had been sparked by the result of the Wrekin by-election three days earlier, when the Conservative Arthur Colegate retained the seat for the party, but with a surprisingly small majority. He had faced an eccentric, if dangerous, far-right candidate, Noel Pemberton Billing, who stood on a platform of ‘Bomb Berlin’ – advocating the defeat of Germany by bombing alone.

It was the latest in a series of disappointing results for the coalition government, with independent candidates tapping into frustration felt by defeats in Greece and Crete, the deadlock in the Middle East, and problems of production at home.

‘It shows the difficulty of fighting under these conditions’, Churchill told the meeting. ‘The Government has to defend everything - they {can merely} criticise and promise everything’.

The Prime Minister had been buoyed by visits to the bombed cities of Liverpool, Coventry and Birmingham on Friday. With enormous satisfaction he recounted that as he toured the shattered streets ‘every single man took off his cap…and in Birmingham the people were delirious’.

Churchill urged ministers to get out and make the National Government’s case more clearly in future by-elections. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Sir Kingsley Wood promised that Conservative Central Office would examine what more could be done – noting, however, that the ubiquitous Pemberton Billing, who was taking part in most by-elections, would also be standing at Hampstead.

The mood of discontent continued when the discussion moved to recent press coverage. The consensus was that the newspapers were seizing on every opportunity to put the Government in a poor light.

Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary, had a swipe against the Daily Express, which was criticising him for refusing to lift certain blackout regulations. Bevin was irritated with the Daily Herald for highlighting manpower problems, an issue he strongly suspected was being driven by his old trade union rival, Walter Citrine. And Anthony Eden had a more general complaint against the Evening Standard and Daily Express for their continual sniping against the Foreign Office. Churchill assured all three he would take ‘a pretty firm line’ with the Government’s critics in his statement to the House of Commons the next day.

The Cabinet’s unduly sensitive mood was reflected in a discussion about the application of Harry Polllitt, Secretary of the Communist Party, to hold a series of lunchtime meetings at war production factories and in Government offices to exhort the workers to increase their output – primarily for the benefit of the beleaguered Soviet Union.

But Sir John Anderson and Ernest Bevin were having none of it. Anderson’s report to the Cabinet reported that the Trade Union movement was already alarmed at extent of penetration by Communist elements. ‘This danger would be substantially increased if Communist leaders were allowed to appeal to the workers for increased production without any appearance of official permission or approval’, Anderson wrote.

A visit from a member of the Armed Services was one thing; a ‘political’ meeting with a lecture from a Communist – or anyone of a radical hue – was quite another. The Cabinet had no hesitation in agreeing to ban this type of meeting from taking place on Government property; as for those offered in private factories, the Trade Union Congress and British Employers’ Federation should be closely consulted.

Perhaps the most worrying news that afternoon concerned the damage German U-boats continued to inflict on the Atlantic convoys. The First Sea Lord, Sir Dudley Pound gave out the grim figures that, since the previous Cabinet four days ago, 54,000 tons of merchant shipping had been lost. The Gibraltar Convoy had lost nine of its 24 ships, and the homeward-bound Sierra Leone convoy had also been attacked and reduced from 11 ships to 4.

‘We need to {consider giving} the ships extra endurance’, the Prime Minister suggested, ‘and they should take a wider sweep’.

The one note of encouragement from what had ultimately been a rather gloomy, at times ill-tempered meeting, lay with the Minister of Supply in Moscow, as he prepared for day two of his talks with Stalin.

‘The atmosphere is propitious’, Churchill reported to the Cabinet, having just received his first briefing from Lord Beaverbrook. Stalin had asked if Britain could provide him with 500 tanks a month: an unlikely target, but the recent ‘Tanks for Russia’ week had seen a twenty per cent rise in output, according to the Ministry of Supply.

The Cabinet also considered disorder in Persia, whether to confirm an order of destroyers and submarines to Turkey, and whether to rescind the current policy of not bombing Rome. The meeting ended with the approval of conditions relating to the sending of US lend-lease aircraft from India to China.

It had been a crisp, well directed, if somewhat tetchy few hours. But there was a feeling in the room of treading water. Sir Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, who was present that afternoon, reflected; ‘Generally, life here is almost like peacetime – no air raids. But dull and depressed’.

Churchill was determined the Government – and the country – should not be lulled into a false sense of security. Much depended on the resistance of the Russians. Here, he was convinced Hitler was building up very large quantities of boats and barges, ready to roll up on to the English beaches and disgorge their tanks and armoured vehicles. The coming winter afforded no assurance that invasion would not take place.

The Prime Minister left the Cabinet Room to return to his desk and polish the concluding passages of his speech for the following day. It would eventually read, soberly but with the usual flourish; ‘Only the most strenuous exertions, a perfect unity of purpose, added to our traditional unrelenting tenacity, will enable us to act our part worthily in the prodigious world drama in which we are now plunged. Let us make sure these virtues are forthcoming’.